Clement-Jones family - Person Sheet

Clement-Jones family - Person Sheet

Birth1719

Death1805

FatherWilliam EVELYN-GLANVILLLE , 1827 (1686-1766)

MotherFrances GLANVILLE , 14338

Spouses

Birth1711

Death1761

FatherHugh BOSCAWEN, 1ST VISCOUNT FALMOUTH , 417 (1680-1734)

MotherCharlotte GODFREY , 451 (1670-1754)

Marriage1742, St Michaels , Cornwall

ChildrenGeorge Evelyn , 1107 (1758-1808)

Elizabeth , 3061 (1747-1828)

Frances , 10863 (1746-1813)

William Glanville , 10864 (1749-1769)

Notes for Frances Evelyn GLANVILLLE

Frances Boscawen was born in 1719 in St. Clere, the only child of Frances Glanville and William Evelyn. William took his wife’s name upon marriage, giving young Frances the last name Glanville. Little is known of her youth and development.

In 1742, Frances married Edward Boscawen, a noted Admiral who later became General of the Marines. Edward’s occupation would prove to be crucial to his wife’s development as a writer. Many of her early letters were written while her husband was away at sea. The couple had five children; two of her sons died tragically while traveling. Frances is known for being a notable domestic and had a reputation as an ideal wife and mother.

After her husband’s death in 1761, Frances became an important hostess of Bluestocking meetings. She was close friends with Elizabeth Montagu, often thought of as “Queen of the Blues”, who was also a hostess of these events. Frances took on the role of typical Bluestocking hostess, in that she used her home to facilitate the exchange of ideas, but published little of her own writing.

Most of Frances’ letters were published after her death in 1805, particularly in William Roberts’ biography of Hannah More (1844). Her letters to her husband, preserved by her family, were published largely in a collection called Admiral’s Wife (1940). A second compilation of her letters was published in 1943, entitled Admiral’s Widow. Most of her letters, however, remain unpublished.

From Wikipedia:

Frances Evelyn Boscawen (née Glanville) (23 July 1719 – 26 February 1805) was known as a literary hostess, correspondent and member of the Bluestockings Society.

Frances Evelyn Glanville was born on 23 July 1719 at St Clere in Kent. In 1742 she married Edward Boscawen (1711–1761). When Edward's work in the navy took him away from home Frances sent him passages from her journal, some of which were later published.

Family

Their children were:

Edward Hugh Boscawen (13 Sept 1744- 1774)

Frances Boscawen (7 March 1746 - 14 July 1801); she married 5 July 1773, aged 27, Admiral Hon. John Leveson-Gower (11 July 1740 - 28 August 1792), younger son of John Leveson-Gower, 1st Earl Gower and half-brother of the 1st Marquess of Stafford and had several children, five sons and two daughters. The heirs male descending of this marriage are in remainder to the earldom of Gower and the baronetcy only.

Elizabeth later Duchess of Beaufort (28 May 1747 Falmouth, Cornwall - 15 June 1828 Stoke Gifford, Gloucestershire); she married 2 January 1866 the Duke of Beaufort at St. George's Church, St. George Street, Hanover Square, London and had eight sons and four daughters with him.[5] She may have been the "Lady in Blue" painted by Thomas Gainsborough.[6]

William Glanville Boscawen (11 August 1749 - 21 April 1769) died aged 19.

George, born 6 May 1758, succeeded his uncle as third Viscount Falmouth in 1782. All the future Viscounts Falmouth and two earls Falmouth are descended from his two sons.

After Boscawen's death in 1761, Frances returned to her London house at 14 South Audley Street, where she became an important hostess of Bluestocking meetings. Her guests included Elizabeth Montagu, Dr Johnson, James Boswell, Joshua Reynolds, Frances Reynolds, Elizabeth Carter, and later Hannah More, who described her as 'sage' in her 1782 poem The Bas Bleu, or, Conversation, published in 1784.[7] Her widowhood inspired Edward Young's 1761 poem Resignation.[1] She "was widely known in literary London as a model letter writer and conversationalist, prized for her wit, elegance, and warm heart," according to a present-day scholar.

Frances died at home in London 26 February 1805.

Brian Sewell in the Evening Standard

Published: 04 April 2008

Almost everything the sane man needs to know about Bluestockings is to be found in the Oxford English Dictionary. The essentials of the long entry are as follows: the term "originated in connexion with the reunions held in London about 1750, at the houses of Mrs Montague, Mrs Vesey and Mrs Ord, who exerted themselves to substitute for the card playing which then formed the chief recreation at evening parties, more intellectual modes of spending the time, including conversation on literary subjects, in which eminent men of letters took part. Many of those who attended eschewed ‘full dress’; one of these was Mr Benjamin Still-ingfleet, who habitually wore grey or ‘blue’ worsted instead of black silk stockings. Admiral Boscawen derisively dubbed the coterie ‘the Blue Stocking Society’ (as not constituting a dressed assembly). The ladies were at first called Bluestockingers, Blue Stocking Ladies, and at length, about 1790, when the actual origin of the term was remembered by few, Blue Stockings Hence, of women, having or affecting literary tastes; literary, learned."

The lexicographers of the 1933 edition of the OED should perhaps have stressed that here blue is the blue of whippets, that is grey, for blue as we generally understand it now was very much the colour of servants’ uniforms. There is not much more to be said, other than that in the 19th century, Bluestocking was a dismissive term for a young woman who spent more time with her books than making herself marriageable, and as an excuse for an older woman’s lack of a husband; in the 20th century it has suggested both an educated frump and the suspicion that a woman might be lesbian.

There is some irony in the coincidence that, in the very week when English universities announced that Women’s Studies are to be discontinued as an academic discipline worthy of a degree (only 10 students remain devoted to it, in only one university, and that one not surprisingly an upgraded polytechnic), the National Portrait Gallery opened a new exhibition devoted to the Bluestockings of the 18th century.

Its curators, women, call it Brilliant Women; they blow feebly on the dying embers of feminism, their subjects the foremothers (as they put it) of Germaine Greer, the forgotten formidable women who, in the Age of Reason, were wealthy enough to open their houses to the literati of their day. Their unquestioning implication is that all these women were intellectually brilliant, but, recalling the praise that Vasari lavished on the charming but unimportant woman painter Sofonisba Anguisciuola two centuries earlier — "most excellent in painting most gifted her portraits ...done with care and spirit appear to be breathing and absolutely alive wanting in nothing save speech" — I suspect that if these women were thought brilliant in their day, it was less for any achievement than that they were women pursuing activities not much expected of them. Sofonisba was no more than adequate as a jobbing painter, and Lavinia Fontana, a generation later, was a great deal worse, yet both were praised by their male contemporaries as brilliant woman worthy of patronage from pope and prince, but this was simply men’s response to that then rare and curious phenomenon, the woman painter. The esteem of their contemporaries should not influence our judgment now.

Of course, in their 18th-century day, it must still have seemed remarkable to men that Angelica Kauffmann painted, that Catharine Macaulay wrote — over two decades — an eight-volume History of England, and that Mary Wollstonecraft was a political force battling for the rights of women, but to us, now, have any of them quite the renown of Reynolds and Gainsborough, Johnson and Gibbon, Burke and Paine? Is not our judgment always, when we compare the achievements of women with those of men, distorted by astonishment, not that they have done so well but that they have done at all? I am reminded of the adage: "A sow may whistle, though it has an ill mouth for it." Would it have made the slightest difference to any of their chosen fields had all three, instead, cultivated gardens, and their friends continued to play cards? What can have been so intellectual in any true sense about the conversation at their informal gatherings? Their contemporaries Fielding and Johnson gave the game away, the first with his "Scandal is the best sweetener of tea" (the favoured drink of Bluestockings), and the second in an exchange with Boswell in which the old man observed after just such a gathering, "Well, we had a good talk," to which his biographer replied, "Yes, sir, you tossed and gored several persons." In a remarkable instance of pot and kettle, Johnson said of Macaulay that she should redden her own cheeks rather than blacken other people’s characters.

I can quite believe that these women were, in their various ways, worthy of interest at the time, but I do not believe that men have conspired to suppress their memory. If we have forgotten Catharine Macaulay’s History of England, it is because the other Macaulay, Thomas Babington, covered the same ground in his equally magisterial work of the mid-19th century, he in turn forgotten in the shadow of Trevelyan, Ogg and Plumb — that is the way of things for all historians. Kauffmann, on the other hand, is always included in relevant exhibitions, and Wollstonecraft is now never neglected in any discussion of the rights of men and women and the equality of the sexes. If other Bluestockings have sunk deep into obscurity, it is not because they were women, but because, if they were brilliant at all, they were not brilliant enough.

It is this that explains the near oblivion of the women identified as The Nine Living Muses of Great Britain in an absurd speculative painting by Richard Samuel in hope of furthering his career, but so weak in portraiture that the women could not recognise their likenesses. In this appear from left to right, Elizabeth Carter, a classical scholar whose reputation lasted just into the 20th century, Anna Letitia Barbault, poet and writer, with Angelica Kauffmann seated at her easel; in the centre stands Elizabeth Sheridan, arguably the greatest English singer of her day and a strenuous supporter of Charles Fox; and to the right, Charlotte Lennox, novelist and advocate of "Studies proper to a Woman", Hannah More, dramatist and writer, Elizabeth Montague, literary critic, Elizabeth Griffith, novelist and playwright, and, seated with a writing tablet on her lap, Catharine Macaulay. Of all these, only Kauffmann’s name might trigger recognition from an educated man on the Clapham omnibus.

Are things different today? Apparently not. The curators of this exhibition, advancing their thesis into contemporary times, can identify for the Clapham-bound traveller only Germaine Greer, but Lord knows as a muse of what. To me, even if she is the author of one of the two great unread books of the 20th century, in the casual and suppositious scholarship of her writings and the blustering and bullying tactics of her debate, she is very different from the Bluestockings of my young day, and I do not think her worthy of the title. Of the nine female vice-presidents of the British Academy, Bluestockings all, I have no doubt, right up to their suspender belts, no commuter from Clapham is ever likely to have heard. Shall I suggest Janet Street-Porter?

Sandy Nairne, director of the NPG, has opined that Bluestockings "are an excellent subject" for the gallery to explore — and so they may be, but this exhibition is absurdly small and gives the impression of three weeks’ work by a couple of undergraduates with access to Wikipedia and an indulgent tutor. It shows us nothing that is a masterpiece, but much that, apart from likeness as a portrait, is of scant value as a work of art. This is indeed jobbing portraiture at its worst. It is a long time since my reaction to a picture was a burst of laughter, but it happened here, in front of the amazingly Plain Jane that Catharine Macaulay was in her mid-forties, shortly before she swapped her protector, then in his mid-seventies, for marriage to a lusty young seaman of 21; an honest view of her it may have been, but the painter made her look ridiculous as well as plain. Even the portrait of Madame de Staël by Elizabeth Vigée-Lebrun (and what is the relevance in this context of a French portrait of a Swiss sitter? — the Swiss provenance, the de Saussure family, is nevertheless particularly intriguing) is weak and grotesquely dis-proportionate; the poor woman was known for her unlovely face rather than her massive thighs.

The prevalence in the NPG of paintings that are of wretched quality yet have important documentary quality presents it with the recurring problem that any exhibition of historic figures that it may choose to mount may well be, as here, wholly unrewarding in aesthetic terms, no matter how important or interesting the subject. The supposedly brilliant women were not well served by the painters of their day and no honest critic could argue a contrary view. The catalogue is even worse. As is now customary, it is a book rather than a catalogue, but as a book it is little more than an adolescent student’s essay, a toe-in-feminist-waters thing, a two-page spread by an amateur in the Saturday Guardian, the tone polemical, and too meagre ever to be a work of reference. A book of brief lives of Bluestockings, whether exhibited or not, would have been infinitely more valuable. How odd, for example, not to have told us more of Elizabeth Sheridan, first wife of the dramatist, a consumptive creature of ineffable beauty and unrivalled voice as well as a thirst for politics, and why not more of Catharine Macaulay, who seems more a woman of our times than her own? In their book the curators quote a feeble verse from the Monthly Review of 1774 naming other women as the Muses — Brooks, Aikin, Greville and Wheatley; of these, Aikin is explained in a distant footnote, but not a word is written of the remaining three. Who was the Mrs Ord listed as a Bluestocking in the OED? And why not a note on the Admiral Edward Boscawen, husband of the Frances Boscawen whose portrait is included in the exhibition (can this weak and very English-seeming thing really be by Ramsay at the age of 35, or any age, for that matter?); as the admiral it was who coined the word Bluestocking, surely Old Dreadnought or Wry-necked Dick, as he was known to his men, deserved to be included?

A little academic rigour, some shrewd editorial advice and a stronger sense of purpose might have made something of this project; as it is, neither the exhibition nor the book amounts to anything.

Brilliant Women is at the National Portrait Gallery (020 7306 0055) until 15 June. Daily 10am-6pm (Thursday and Friday until 9pm). Admission free (www.npg.org.uk).

Brilliant Women: Bluestockings

National Portrait Gallery

St Martin's Place, WC2H 0HE

In 1742, Frances married Edward Boscawen, a noted Admiral who later became General of the Marines. Edward’s occupation would prove to be crucial to his wife’s development as a writer. Many of her early letters were written while her husband was away at sea. The couple had five children; two of her sons died tragically while traveling. Frances is known for being a notable domestic and had a reputation as an ideal wife and mother.

After her husband’s death in 1761, Frances became an important hostess of Bluestocking meetings. She was close friends with Elizabeth Montagu, often thought of as “Queen of the Blues”, who was also a hostess of these events. Frances took on the role of typical Bluestocking hostess, in that she used her home to facilitate the exchange of ideas, but published little of her own writing.

Most of Frances’ letters were published after her death in 1805, particularly in William Roberts’ biography of Hannah More (1844). Her letters to her husband, preserved by her family, were published largely in a collection called Admiral’s Wife (1940). A second compilation of her letters was published in 1943, entitled Admiral’s Widow. Most of her letters, however, remain unpublished.

From Wikipedia:

Frances Evelyn Boscawen (née Glanville) (23 July 1719 – 26 February 1805) was known as a literary hostess, correspondent and member of the Bluestockings Society.

Frances Evelyn Glanville was born on 23 July 1719 at St Clere in Kent. In 1742 she married Edward Boscawen (1711–1761). When Edward's work in the navy took him away from home Frances sent him passages from her journal, some of which were later published.

Family

Their children were:

Edward Hugh Boscawen (13 Sept 1744- 1774)

Frances Boscawen (7 March 1746 - 14 July 1801); she married 5 July 1773, aged 27, Admiral Hon. John Leveson-Gower (11 July 1740 - 28 August 1792), younger son of John Leveson-Gower, 1st Earl Gower and half-brother of the 1st Marquess of Stafford and had several children, five sons and two daughters. The heirs male descending of this marriage are in remainder to the earldom of Gower and the baronetcy only.

Elizabeth later Duchess of Beaufort (28 May 1747 Falmouth, Cornwall - 15 June 1828 Stoke Gifford, Gloucestershire); she married 2 January 1866 the Duke of Beaufort at St. George's Church, St. George Street, Hanover Square, London and had eight sons and four daughters with him.[5] She may have been the "Lady in Blue" painted by Thomas Gainsborough.[6]

William Glanville Boscawen (11 August 1749 - 21 April 1769) died aged 19.

George, born 6 May 1758, succeeded his uncle as third Viscount Falmouth in 1782. All the future Viscounts Falmouth and two earls Falmouth are descended from his two sons.

After Boscawen's death in 1761, Frances returned to her London house at 14 South Audley Street, where she became an important hostess of Bluestocking meetings. Her guests included Elizabeth Montagu, Dr Johnson, James Boswell, Joshua Reynolds, Frances Reynolds, Elizabeth Carter, and later Hannah More, who described her as 'sage' in her 1782 poem The Bas Bleu, or, Conversation, published in 1784.[7] Her widowhood inspired Edward Young's 1761 poem Resignation.[1] She "was widely known in literary London as a model letter writer and conversationalist, prized for her wit, elegance, and warm heart," according to a present-day scholar.

Frances died at home in London 26 February 1805.

Brian Sewell in the Evening Standard

Published: 04 April 2008

Almost everything the sane man needs to know about Bluestockings is to be found in the Oxford English Dictionary. The essentials of the long entry are as follows: the term "originated in connexion with the reunions held in London about 1750, at the houses of Mrs Montague, Mrs Vesey and Mrs Ord, who exerted themselves to substitute for the card playing which then formed the chief recreation at evening parties, more intellectual modes of spending the time, including conversation on literary subjects, in which eminent men of letters took part. Many of those who attended eschewed ‘full dress’; one of these was Mr Benjamin Still-ingfleet, who habitually wore grey or ‘blue’ worsted instead of black silk stockings. Admiral Boscawen derisively dubbed the coterie ‘the Blue Stocking Society’ (as not constituting a dressed assembly). The ladies were at first called Bluestockingers, Blue Stocking Ladies, and at length, about 1790, when the actual origin of the term was remembered by few, Blue Stockings Hence, of women, having or affecting literary tastes; literary, learned."

The lexicographers of the 1933 edition of the OED should perhaps have stressed that here blue is the blue of whippets, that is grey, for blue as we generally understand it now was very much the colour of servants’ uniforms. There is not much more to be said, other than that in the 19th century, Bluestocking was a dismissive term for a young woman who spent more time with her books than making herself marriageable, and as an excuse for an older woman’s lack of a husband; in the 20th century it has suggested both an educated frump and the suspicion that a woman might be lesbian.

There is some irony in the coincidence that, in the very week when English universities announced that Women’s Studies are to be discontinued as an academic discipline worthy of a degree (only 10 students remain devoted to it, in only one university, and that one not surprisingly an upgraded polytechnic), the National Portrait Gallery opened a new exhibition devoted to the Bluestockings of the 18th century.

Its curators, women, call it Brilliant Women; they blow feebly on the dying embers of feminism, their subjects the foremothers (as they put it) of Germaine Greer, the forgotten formidable women who, in the Age of Reason, were wealthy enough to open their houses to the literati of their day. Their unquestioning implication is that all these women were intellectually brilliant, but, recalling the praise that Vasari lavished on the charming but unimportant woman painter Sofonisba Anguisciuola two centuries earlier — "most excellent in painting most gifted her portraits ...done with care and spirit appear to be breathing and absolutely alive wanting in nothing save speech" — I suspect that if these women were thought brilliant in their day, it was less for any achievement than that they were women pursuing activities not much expected of them. Sofonisba was no more than adequate as a jobbing painter, and Lavinia Fontana, a generation later, was a great deal worse, yet both were praised by their male contemporaries as brilliant woman worthy of patronage from pope and prince, but this was simply men’s response to that then rare and curious phenomenon, the woman painter. The esteem of their contemporaries should not influence our judgment now.

Of course, in their 18th-century day, it must still have seemed remarkable to men that Angelica Kauffmann painted, that Catharine Macaulay wrote — over two decades — an eight-volume History of England, and that Mary Wollstonecraft was a political force battling for the rights of women, but to us, now, have any of them quite the renown of Reynolds and Gainsborough, Johnson and Gibbon, Burke and Paine? Is not our judgment always, when we compare the achievements of women with those of men, distorted by astonishment, not that they have done so well but that they have done at all? I am reminded of the adage: "A sow may whistle, though it has an ill mouth for it." Would it have made the slightest difference to any of their chosen fields had all three, instead, cultivated gardens, and their friends continued to play cards? What can have been so intellectual in any true sense about the conversation at their informal gatherings? Their contemporaries Fielding and Johnson gave the game away, the first with his "Scandal is the best sweetener of tea" (the favoured drink of Bluestockings), and the second in an exchange with Boswell in which the old man observed after just such a gathering, "Well, we had a good talk," to which his biographer replied, "Yes, sir, you tossed and gored several persons." In a remarkable instance of pot and kettle, Johnson said of Macaulay that she should redden her own cheeks rather than blacken other people’s characters.

I can quite believe that these women were, in their various ways, worthy of interest at the time, but I do not believe that men have conspired to suppress their memory. If we have forgotten Catharine Macaulay’s History of England, it is because the other Macaulay, Thomas Babington, covered the same ground in his equally magisterial work of the mid-19th century, he in turn forgotten in the shadow of Trevelyan, Ogg and Plumb — that is the way of things for all historians. Kauffmann, on the other hand, is always included in relevant exhibitions, and Wollstonecraft is now never neglected in any discussion of the rights of men and women and the equality of the sexes. If other Bluestockings have sunk deep into obscurity, it is not because they were women, but because, if they were brilliant at all, they were not brilliant enough.

It is this that explains the near oblivion of the women identified as The Nine Living Muses of Great Britain in an absurd speculative painting by Richard Samuel in hope of furthering his career, but so weak in portraiture that the women could not recognise their likenesses. In this appear from left to right, Elizabeth Carter, a classical scholar whose reputation lasted just into the 20th century, Anna Letitia Barbault, poet and writer, with Angelica Kauffmann seated at her easel; in the centre stands Elizabeth Sheridan, arguably the greatest English singer of her day and a strenuous supporter of Charles Fox; and to the right, Charlotte Lennox, novelist and advocate of "Studies proper to a Woman", Hannah More, dramatist and writer, Elizabeth Montague, literary critic, Elizabeth Griffith, novelist and playwright, and, seated with a writing tablet on her lap, Catharine Macaulay. Of all these, only Kauffmann’s name might trigger recognition from an educated man on the Clapham omnibus.

Are things different today? Apparently not. The curators of this exhibition, advancing their thesis into contemporary times, can identify for the Clapham-bound traveller only Germaine Greer, but Lord knows as a muse of what. To me, even if she is the author of one of the two great unread books of the 20th century, in the casual and suppositious scholarship of her writings and the blustering and bullying tactics of her debate, she is very different from the Bluestockings of my young day, and I do not think her worthy of the title. Of the nine female vice-presidents of the British Academy, Bluestockings all, I have no doubt, right up to their suspender belts, no commuter from Clapham is ever likely to have heard. Shall I suggest Janet Street-Porter?

Sandy Nairne, director of the NPG, has opined that Bluestockings "are an excellent subject" for the gallery to explore — and so they may be, but this exhibition is absurdly small and gives the impression of three weeks’ work by a couple of undergraduates with access to Wikipedia and an indulgent tutor. It shows us nothing that is a masterpiece, but much that, apart from likeness as a portrait, is of scant value as a work of art. This is indeed jobbing portraiture at its worst. It is a long time since my reaction to a picture was a burst of laughter, but it happened here, in front of the amazingly Plain Jane that Catharine Macaulay was in her mid-forties, shortly before she swapped her protector, then in his mid-seventies, for marriage to a lusty young seaman of 21; an honest view of her it may have been, but the painter made her look ridiculous as well as plain. Even the portrait of Madame de Staël by Elizabeth Vigée-Lebrun (and what is the relevance in this context of a French portrait of a Swiss sitter? — the Swiss provenance, the de Saussure family, is nevertheless particularly intriguing) is weak and grotesquely dis-proportionate; the poor woman was known for her unlovely face rather than her massive thighs.

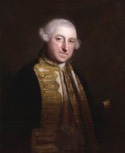

The prevalence in the NPG of paintings that are of wretched quality yet have important documentary quality presents it with the recurring problem that any exhibition of historic figures that it may choose to mount may well be, as here, wholly unrewarding in aesthetic terms, no matter how important or interesting the subject. The supposedly brilliant women were not well served by the painters of their day and no honest critic could argue a contrary view. The catalogue is even worse. As is now customary, it is a book rather than a catalogue, but as a book it is little more than an adolescent student’s essay, a toe-in-feminist-waters thing, a two-page spread by an amateur in the Saturday Guardian, the tone polemical, and too meagre ever to be a work of reference. A book of brief lives of Bluestockings, whether exhibited or not, would have been infinitely more valuable. How odd, for example, not to have told us more of Elizabeth Sheridan, first wife of the dramatist, a consumptive creature of ineffable beauty and unrivalled voice as well as a thirst for politics, and why not more of Catharine Macaulay, who seems more a woman of our times than her own? In their book the curators quote a feeble verse from the Monthly Review of 1774 naming other women as the Muses — Brooks, Aikin, Greville and Wheatley; of these, Aikin is explained in a distant footnote, but not a word is written of the remaining three. Who was the Mrs Ord listed as a Bluestocking in the OED? And why not a note on the Admiral Edward Boscawen, husband of the Frances Boscawen whose portrait is included in the exhibition (can this weak and very English-seeming thing really be by Ramsay at the age of 35, or any age, for that matter?); as the admiral it was who coined the word Bluestocking, surely Old Dreadnought or Wry-necked Dick, as he was known to his men, deserved to be included?

A little academic rigour, some shrewd editorial advice and a stronger sense of purpose might have made something of this project; as it is, neither the exhibition nor the book amounts to anything.

Brilliant Women is at the National Portrait Gallery (020 7306 0055) until 15 June. Daily 10am-6pm (Thursday and Friday until 9pm). Admission free (www.npg.org.uk).

Brilliant Women: Bluestockings

National Portrait Gallery

St Martin's Place, WC2H 0HE